Shahriyor Abdubakiev

Image source: www.kun.uz

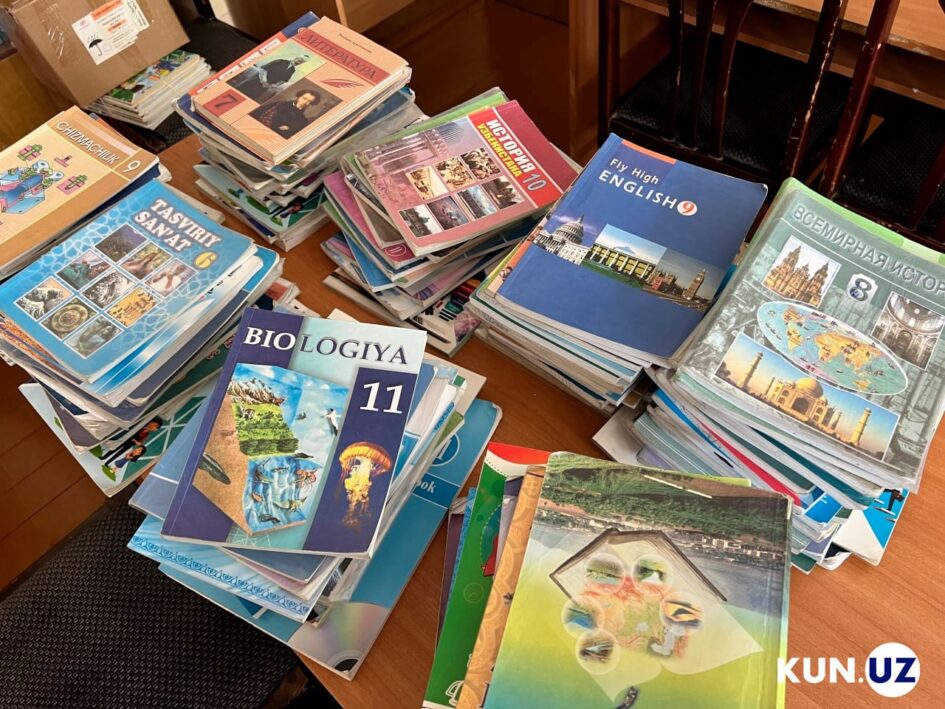

Chapter IX, Article 41 of the Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan says that the state guarantees free general education to the citizens of Uzbekistan. However, it is no secret that it takes money to rent textbooks in secondary schools. The sudden increase in the price of textbooks in September 2022 caused great controversy among the population. Kusherbayev, a prominent deputy on his telegram channel, raised such a question. “Why should textbooks be paid for, since general education is defined in the Constitution as free?” he asked. How should the constitutional norm on this issue be interpreted and implemented?

What happened?

This year (September 2022) in Uzbekistan, a sharp increase in the price of rent of textbooks for general secondary education has caused serious complaints among citizens. That is, the average rent of one textbook (workbook) this year makes 5707 soums, and compared to last year’s amount (2740 soums), it has increased by 2967 soums (208%). At the same time, the minimal rental price was 68.5 thousand soums, and the maximal price was 119.8 thousand soums. This price may not be costly, but the Uzbek people have many children. Some families raise up to 4 children. Naturally, this amount is quite expensive for them. It is understandable if private schools rent textbooks for a fee, but this issue should be considered in public schools.

So why did textbooks become more expensive?

According to the information service of the Ministry of Public Education, the cost of printing textbooks has risen sharply. In 2022, the price of paper worldwide has risen by 60-70%, and import transportation costs have risen sharply. On the other hand, the media have raised some serious questions over corruption concerns.

In addition, Mr. Rasul Kusherbayev, a prominent member of the UzLiDeP party in parliament, responded to the situation to provide a legal assessment of the issue. According to him, these rent payments contradict the Constitution, and he stated that he would appeal to the Constitutional Court to review this issue. The Constitutional Court has yet to rule on the matter. After the issue raised widespread objections, President Mirziyoyev issued an order on September 5 to accelerate the free textbook rental.

Even though the problem has been solved by administrative methods, if the Constitutional Court handles this case, it is essential to analyze from a legal point of view on what grounds and how it will make a decision.

Article 41 of the Constitution

Article 41 of the Constitution establishes the following norm:

“Everyone has the right to education. The state guarantees free general education. School affairs are under state control.”

The article mentioned above is stipulated by the recently adopted Law “On Education” (2020). Article 5 of this law specifies that the state will provide general secondary, secondary specialized, and primary vocational education free of charge. In addition, article 47 of the same law confirms the above opinion. Nevertheless, the state authorities have not published the official commentary on Article 41 of the Constitution.

Below I will explain some of the legal arguments before moving to my conclusion.

First, the textbook rental system was introduced not immediately after the adoption of the Constitution in 1992 but since 2006. Presidential Decree No. PD-362, “On the Procedure for Leasing Textbooks on an Experimental Basis” was enacted on May 31, 2006. This decision aimed to further develop the system of providing students in general education schools with textbooks, improving the mechanism of ordering and renting textbooks, and organizing a vast network of retail sales of textbooks. In addition, a mechanism for selling textbooks in the Republic was carried out as an experiment. However, later this system was preserved in a permanent form.

As you can see, initially, the textbooks were free of charge, and later (in 2006), as an experiment, the system of paid rent was introduced. It is important to note that the Presidential Decree also noted that for representatives of specific categories of students, such as 1st-year students, adopted children of the “Mehribonlik” homes, the poor, and the population in need of other social protection, textbooks will be free of charge. Also, Part 8¹ of this decision gave strict instructions not to allow unreasonable increases in the price of books. In the end, as a natural question, one should ask, why has it not been paid since the adoption of the Constitution in 1992?

Second, the author of the leading textbook on “Constitutional Law,” Professor Husanov, also interprets Article 41 broadly:

“Everyone has the right to education, which means that all people living in the country, regardless of citizenship, nationality, race, religion, gender, etc., enjoy this right. According to the Constitution, free education is provided by the state. In our country, primary and general secondary education is free, and all costs are covered by the state.”(Husanov)

Commentary on the theory of interpretation of Article 41

But suppose we rely on methods of grammatical interpretation and logical interpretation of legal norms. In that case, every person living in Uzbekistan, regardless of race, nationality, religion, social origin, presence or absence of citizenship, or physical abilities, has the right to receive education appropriately (in special schools). The general education process is free of charge, i.e. (organization of classrooms, equipment, employment of teachers, payment of salaries, provision of school books, etc.) and is provided by the state. Any processes carried out in the school are controlled and managed by the state.

Moreover, suppose we recall the article by the Japanese jurist Makoto Itoh in his book “The Guide to study Law,” using literal and expansive interpretations of the law. In that case, the notion that the state guarantees free public education is greatly expanded. Even if we interpret the law in a teleological (purposive) way, all of the above types of interpretation give the same meaning. That is, it turns out that the state has taken it upon itself to provide schoolbooks, lunches, clothing, school supplies, and more. In order to solve the problem (to reveal its true content), the Oliy Majlis (Parliament) or the Constitutional Court must interpret Article 41 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to free general education.

In fact, this question reinforces other questions of approach. For example, how about the school uniform? Is it free, too? What about school lunch? If we rely on the teleological (purposive) method of legal interpretation, we can add these issues (school uniforms, school lunches) to the process of free general education. Therefore, the state is obliged to provide them free of charge based on Article 41.

Summary

In this article, I examined the constitutionality of charging for school textbooks in Uzbekistan. Although Article 41 provides the right to free education, it was revealed that there is no official commentary on this article, and no clear conclusion can be heard from official bodies. Based on various methods of interpretation, I concluded that the state should provide free textbooks in schools. But for now, we are left to wait for official clarification from the Parliament or Constitutional Court on this matter.

Cite as: Shahriyor Abdubakiev, “Constitutionality of school textbooks rentals”, Uzbekistan Law Blog, 01.12.2022.

Leave a Reply