by Mironshokh Murodilloev

Image source: journalsofindia.com

December 18,2021

Regardless of the fact that IIAs have been adopted almost universally, there is no global investment treaty or rule of customary international law that would obligate States to grant identical rights to investors irrespective of their country of origin. As a consequence, investors’ legal stance relative to the State can vary. To obtain the most favorable investment protection in the patchwork of IIAs, a growing number of investors have resorted to treaty shopping, through which they restructure their business or investment in order to gain access to desirable treaty provisions and dispute settlement mechanisms, for which they would not be qualified otherwise.

In August 2019 under the resolution of the Olmazor Mayer, the area of the former park named after “Gafur Gulam” was given for the foreign investor whose real assets came from the inside of the state while BMP Smart Decision LTD (Singaporean company) was only incorporated in the territory of Singapore. This, in turn, created a massive discontent by the Uzbek segment arguing there was an element of fraud. In order to define whether there was fraud or not, we must sink deeper into the field of international investment law sphere in which the theory of “treaty shopping” and “round-tripping” is covered.

As a starting point, it is important to note that despite the bad publicity and increasingly expressed dissatisfaction among States, treaty shopping is not per se prohibited or even improper under international investment law. Returning to the definition of treaty shopping, the term most often refers to the conduct of foreign investors who deliberately shop for a “home country of convenience” that has favorable IIAs with the host country where their investments are or will be made. The shopping is carried out by altering corporate structures or routing investments through the country necessary to gain access to an IIA even if there is none in place between the host State and the investor’s actual home State. Alternatively, if such IIA exists, investors may “shop” to acquire the benefits of a more favorable IIA.

As an example, take a company operating in X state which is regarded as the home state. There is an IIA between states X and Y, in which the investor is willing to set up investment assets to operate. However, there is another BIT between countries Y and Z containing more favorable investment protection guarantees and privileges towards foreigners. In order to acquire such advantages of Y-Z BIT provisions, the investor happens to own a company in the territory of Z. The next step is to introduce himself as an investor came from Z. The investor thus “planned” its nationality in order to gain the highest level of protection available. To summarize, the Treaty Shopper aims for maximum protection of the investment under the operative treaties.

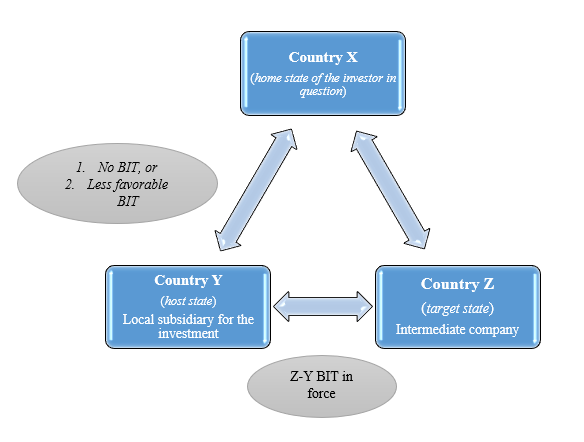

There are two types of treaty shopping that enhance the investors’ position in the case of investment operation: i) the investor’s home State (Country X) does not have a BIT with the host State (Country Y) but a third State (Country Z) has, or ii) Country X has a valid BIT with Country Y but the provisions under the BIT between Country Z and Country Y are more advantageous. In effect, the investor seeks to become national of Country Z and thus eligible for treaty protection under the BIT in question. The following figure illustrates these two situations:

In terms of the legality of this shopping, the essence of the actions and timing should not be underestimated. Accordingly, some have used the terms “back end” and “front end” treaty shopping to describe the classification. “Back end” refers to situations where the investor performs nationality changing arrangements after the investment is already under some imminent threat (for instance, revocation of a license or termination of a contract) or even after the dispute between the host State and the legal entity has already materialized. As for “front end” type, the phrasing means that the foreign investor plans its nationality in advance pursuant to the BIT of convenience. The former is attracted many reactions by most arbitral tribunals putting the legality of the action under doubt with dispute, whereas the latter one is considered to be permissible under pragmatic theory.

The issue in the case above, BMP Smart Decision LTD, the treaty shopping happened before the operation of the investment (“front end” position). As far as international investment law is a part of Public International Law, it is appropriate to order applicable sources embodied in Article 38 of the Statute of International Court of Justice: 1) International treaties, customs, general principles, and judicial decisions. Therefore, it is better to look at the BIT between Uzbekistan and Singapore before prejudicing the investment.

Under Article 1(3) of the very BIT (hereinafter BIT), “an investor is a company that is incorporated under applicable law in force in either party’s territory”. As can be seen, the only requirement for the investor to be regarded as a foreigner and the assets Foreign Direct Investment test “incorporation test” is set. Understanding the concept of nationality and its importance in investment law is crucial in order to fully examine the issues of this research. In fact, nationality has multiple functions when it comes to protecting foreign investments. The vast majority of investment law’s substantive and procedural guarantees are contained in IIAs.

According to this approach, juridical persons that are incorporated or constituted in accordance with the laws of a particular State are considered to be nationals of that State. Consequently, the incorporation test covers investors that are established and organized according to the relevant national legislation. No additional requirements apply, so the corporation can be owned by nationals of a third State or even nationals of the host State itself. Furthermore, the test does not oblige the corporation to exercise any real economic activity in the contracting State, which means that “mailbox” or “shell” companies are deemed to be investors as well, provided that the formal prerequisites are met. Therefore, the very BMP company is required only duly incorporation in a foreign state, but not other requirements, such as carrying out business activities or foreign control. Even if the dispute arises, tribunals tend to apply tenant principles, in particular, Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on Legal Treaties in which the norm is “to interpret provision with ordinary meaning”. Setting additional requirements by the arbitrators is nothing from taking risks: as the Annulment Committee for CMS Award held that the treaty should have been interpreted as it stood. Even, other tribunals like Saluka also concluded tribunals ought to refrain to create laws neither explicitly nor implicitly mentioned in the applicable agreement.

Even under Article 3 of the Law On Investment and Investment activities, the incorporation test is required for foreign investors. Therefore, the BMP Smart Decision LTD holds dual protection under both domestic and international law.

PARADOX

However, one should not be underestimated that BMP company is not a purely foreign company, but it is a “small box” acquiring financial funding within the territory of Uzbekistan which principle is called reciprocity. The reciprocity can also be infringed in a situation where corporate restructuring is utilized to internationalize a domestic dispute. Local investors may benefit from investment protection offered only to foreign investors by channeling investments through other States. Consequently, nationals of the host state can create a scenario where “a company is legally that of a contracting state (home state), while financially it is that of the host State” and opens the door to investment treaty claims against their country of origin. This scheme can be seen contrary to the character and spirit of the BITs and the very purpose of ISDS. In other words, states most sign BITs to attract more money inflow from another contracting state (from Singapore in the case) while all funding inflow is within the territory of Uzbekistan.

Therefore, most scholars coming upon the current practice suggest drafters set up stricter requirements, for example, the investor must be carrying out substantial business activities in the home state. For greater certainty, Uzbekistan made such an arrangement deliberately. As can be seen, the incorporation test is convenient and more effective to attract foreign investment, Uzbekistan might also intend to attract more Singaporean investors.

CONCLUSION

By way of conclusion, certain concluding remarks should be remarked in order to prevent such unfair actions which do not affirm the true aim of foreign direct investment.

Firstly, treaty shopping is, generally, permissible and the best way to boost the investment inflow towards the state economy. Simultaneously, investors also have a great opportunity to expand their routines throughout the world.

Secondly, and in a contrasting manner, so as to prevent such unfair treaty shopping by “mail box” companies, Uzbekistan needs to set more sophisticated requirements towards the nationality of the investor other than the “incorporation” test.

Cite as: Mironshokh Murodilloev, “Treaty shopping under Uzbekistan’s bits and unfairness by “mail box” enterprises”, Uzbekistanlawblog, 18.12.2021

Leave a Reply